by Mary Bailey

In a little more than two decades New Zealand’s Central Otago region has rocketed into winelovers’ consciousness. It couldn’t look more different from most wine regions, especially in the sub-regions near Cromwell. Vineyards do not stretch as far as the eye can see. They nestle on curvy north-facing sites or run down sloping ridges to catch the sun. Total production is small, and high quality. New Zealand’s signature grape variety Sauvignon Blanc is not king here. The crown belongs to Pinot — Noir and Gris, and their cool-climate friends Chardonnay and Riesling. For lovers of these grape varieties, it is heaven on earth.

Rudy claps his hands. Above us on the ridgeline a dozen floppy eared heads pop up and hop away. He claps again and another dozen heads pop up. It’s as if we’re playing some sort of clap-a-mole. “Rabbits dig holes and eat trunks,” Rudy says. “The whole property is rabbit-fenced.” We look down the slope towards Lake Dunstan. Nothing but vines, wind-scuffed hills, rabbits, and vivid blue sky everywhere you look; a magnificent landscape golden in the autumn light.

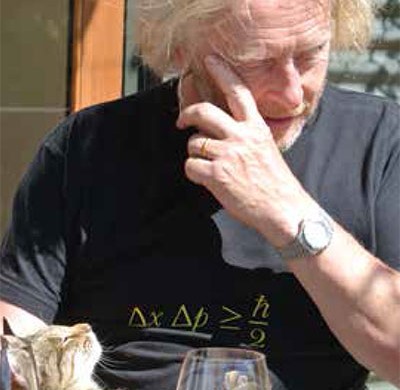

We’re standing near the bottom of Rudy Bauer’s Bendigo vineyard, Central Otago, New Zealand’s south island region carving out a stellar wine reputation for, in particular, amazing pinot noir.

Rudy has played an immense part in creating that rep, first at Rippon, the Wanaka estate that brought this remote area to the attention of pinophiles, and now here. He established Quartz Reef in 1996.

“When I first saw this land in Bendigo in 1991 nothing was planted. I had a vision that it could be a beautiful vineyard.”

The slope’s incline was similar to vineyards he was familiar with in Burgundy and the soil, clay and fine gravel over a seam of quartz, ideal for wine growing. Rudy farms the land biodynamically*, in his experience the best way to bring out the soil’s characteristics in the wine.

We walk through the vines, Rudy pointing out where this season’s bad weather at flowering had caused uneven ripening. Snip snip, and the not-quite-ready bunches fall to the ground. Picking for sparkling wine starts in a week or so and anything malformed or not ripe has to go. The rows are covered in soft netting, so we duck under to move around. It’s bird protection, as thirsty wine drinkers are not the only ones that want to get their beaks into the pristine fruit.

Other than these few unripe bunches the vines that march up this seam of quartz stone from lake to ridgeline look superb, with just the right amount of leaves and healthy fruit.

About 60 per cent of production is still wine, Pinot Gris and Pinot Noir. The rest is devoted to traditional method sparkling wines, a brut and a rosé, from Pinot Noir. (The brut has some Chardonnay for balance).

The intention wasn’t to make sparkling wine, or perhaps not to become so well-known for the bubble that people forget his heart is in Pinot Noir first and foremost. If that is Rudy’s burden we’re happy to share it.

“Everything about this place, the soil, the climate, how the grapes ripen, lends itself to sparkling wine. But as the vines age we’ll get to know what Pinot can really do here.”

Rudy’s other project is Gruner Veltliner, though so far he hasn’t been happy with the results. “Maybe next year,” he says.

Felton Road is at the other end of the Cromwell growing area in Bannockburn. The wide-open terrain of Bendigo is no longer. Here, badlands dotted in wild thyme blanket the scars left behind by 19th century sluice mining. Now, vineyards growing cool-climate varietals cover hillsides.

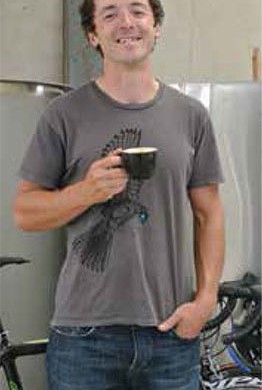

“Stewart Elms picked a good site,” says Mike Wolfenden, assistant winemaker at Felton Road. We’re standing in the home vineyard near the winery. Stewart Elms had identified these north-facing slopes in Bannockburn as the warmest suitable for premium grapes in 1991.

Felton Road farms three sites; Elms, near the winery, Calvert, two blocks just across the road (leased) and Cornish Point on a tip of land that juts out into Lake Dunstan near Cromwell.

It’s holy ground. Some might say that Felton Road is the Romanée Conti of New Zealand (being one of two vineyards designated Tipuranga Teitei o Aotearoa, New Zealand Grand Cru status.) But that’s not what they talk about at the winery. There are no t-shirts, nor promo campaigns promoting the status. They talk about grapes, what’s happening down each row. They make coffee. They act normally, another reminder that great wine is generally made by good people.

I join a group of wine aficionados from Sweden as Mike guides a tasting of wines in barrel and tank. I listen along to Mike and the translator thinking how many wine words remain untranslated — cuvée is cuvée and pinot noir is pinot noir, loess becomes glacial till, still understandable to a Canadian. I am feeling pretty cocky about my wine linguistic ability until I poke my nose into the barrel sample.

All words fail. It’s sensory overload as the wine tells me who it is and where its from in a language all its own.

* Both Felton Road and Quartz Reef farm biodynamically, a philosophical agricultural concept created by Rudolph Steiner in the 1930s. One of the requirements of the practice is a voodoo lounge (actually just a shed, just an ordinary open-walled shed) where soil preparations are made from plants, minerals and compost. The practices are intriguing, to say the least. Most of the biodynamic wines I’ve tasted are different — they have a certain something-something — more communicative, more layered, more interesting. Not always, not every wine. Hard to quantify, but it’s there.